A few people might dismiss them as ‘boring’ because they lack flowers, but ferns are anything but boring – the diversity of sizes and forms makes sure of that. These plants are truly indispensable in all but the hottest and driest of gardens, and for foliage beauty in shady places they are unsurpassed. Some people put in shrubs and trees and then stop, but adding a lower level to your planting makes it so much richer and beautiful. If you can do that without adding significantly to the work of your garden, and do it with plants of great beauty, then who wouldn’t? There are lots of plants that will do that well in sunnier spots, but what about shade? If it isn’t too dry, the answer is, ‘ferns’.

The beauty of ferns is mainly in the diversity of the forms of their leaves – called fronds. Only a few have colored fronds even for part of the year, so fern-beauty about what designers call ‘texture’ – bold arching fronds, or finely divided ‘ferny’ ones. Size and density of foliage play a part too, creating an incredible range of textures to admire – and to enrich the landscape of your garden.

With a few exceptions ferns are plants for shady places, either partial shade or full, deeper shade. They will often grow where nothing else will, and grow profusely too. They only ask for some moisture, and with that you can transform those darker places into wonderlands of beauty. They need so little work that you can grow them abundantly without adding significantly to your chores in the garden. There are many places you can plant them, and lots of ways to use them to improve and beautify your garden. Here are some ideas:

Ferns are not flowering plants, so they don’t have the usual ‘branches, leaves and flowers’ we see on most of our garden plants. They first appeared nearly 400 million years ago, long before flowering plants, and some have remained unchanged for almost 200 million years. They vary in size from an inch or so to several feet tall, but most that are grown in gardens are between 1 and 4 feet tall. There are also much taller tree ferns that will grow outdoors in warmer zones, but the trunk isn’t made the same way as a tree’s. It’s a build-up of the bases of the stems, and a mass of roots, and doesn’t become significantly thicker with age – more like a palm tree.

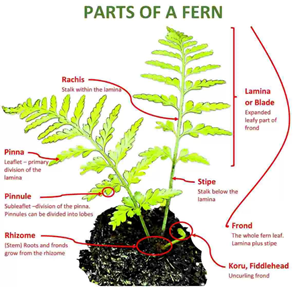

Take a look at this diagram and see the important parts of a fern – it makes talking about them much easier.

Frond – the whole fern ‘leaf’, from top to bottom.

Rachis – the central stalk of the frond.

Stipe – the lower part of the frond, without any ‘leaves’.

Blade – the upper part of the frond, carrying leaflets.

Fiddlehead or Crozier – the young frond as it is uncurling and spreading out the leaflets.

Pinna – (plural: Pinni) the leaflets of the fern. These are often subdivided into smaller leaflets, called Pinnules.

Ferns can be deciduous, with the fronds dying in fall, and a complete new set growing in spring. Others – usually from warmer zones – are evergreen, and the fronds last a long time, finally yellowing and dropping at just about any time of the year. Some evergreen ferns are damaged in colder zones, and behave more like deciduous ferns, while some deciduous ones keep many fronds when grown in warm zones.

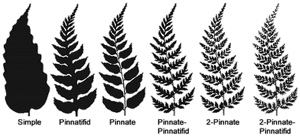

Fern fronds are divided in different ways, depending on how many Pinnules there are. These are the names for them. That -ifid ending means

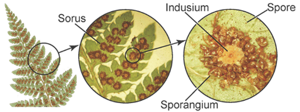

Ferns don’t have flowers, but they do produce spores on the underside of their leaves in areas called Sori (singular: Sorus). These small patches form patterns used for identification. The sorus has a ‘lid’ called an Indusium. The sori are not usually important in the garden, but in some ferns they are colorful, such as the Autumn Fern, Dryopteris erythrosora, with bright red indusia. Although usually carried

OK, enough lessons! Class dismissed!

Wherever you live in this country you can grow ferns. There are some that grow in zones 2 and 3, while others only grow in zones 8 and 9. Most grow across many zones, and usually don’t have complex requirements for ‘chilling hours’ or anything.

Some ferns can grow in full sun, as long as the soil is moist, and this is more likely to work in cooler zones. For most ferns, partial or full shade is preferred – exactly what makes them so valuable in our gardens. Some morning sun is usually OK, and you will see that some ferns do better than others in those very dark corners beneath large evergreens. Almost all love the dappled shade beneath deciduous trees. Generally speaking you can go ahead and plant ferns in any shady part of your garden and expect success.

Ferns usually grow in fibrous, rich soils that are moist but have some drainage. Some will grow in wet soils, and most will grow just fine in ordinary garden soils. Some soil preparation, adding compost, rotted leaves or other forms of organic material will make a huge difference. Although some will grow in alkaline soils, most prefer neutral to slightly acidic ones, but are not fussy that way an azalea is. Usually when grown in pots it’s best to choose potting soils for azaleas and camellias – they seem to work better for ferns.

All ferns love plenty of water, and areas that are always dry are not going to be suitable. The more sunlight the more water is needed, but some kinds of ferns, once established, will take drier conditions. Watch the angle of the fronds. If they are looking as the d the day after watering – probably rising up and arching over a little – then they are fine. If you see that angle begin to fall, get out and water right away. Luckily with most ferns, if the fronds do dry out, a good soak will soon bring back new stems, as long as it isn’t late in the season. Don’t let that happen too often, though, as it weakens the plants.

Soak the pots containing your new ferns with plenty of water the evening before. After preparing the soil and digging it over, plant at the same depth, or an inch deeper, than they are in the pots. Water really well, soaking the ground. Mulch with some of the organic material you used to prepare the ground. It is important to water new plantings frequently, but you can gradually taper off to the recommendations for the mature plant after a few weeks.

The good news on this front is that almost all ferns have no noticeable pests, and diseases only occur when they are in poor drainage – rots of the crown can kill them when that happens. Most are untouched by deer or rabbits too – good news, huh?

Ferns really are among the least demanding of all plants. All they need is to have dead fronds removed, usually once a year. Do this at any time, but remember it is easier when the ferns are dormant, and not producing new leaves – don’t leave it too late in the spring, or do it as part of your fall cleanup.

Our collections of ferns vary from season to season, so we will look at the most widely-grown fern groups that are most likely to be used in gardens.

Adiantum – These are easily recognized, by their black stems and many pinnules on finely-divided stems. The most famous and well-known is the MaidenHair Fern, Adiantum capillus-veneris, with its exquisite fronds divided into many pinnules, forming large arching fronds. It is native all across the south, from California to Florida, and hardy outdoors in zone 7. It’s very widely-grown as a houseplant, but it’s a good garden fern too. It can be tricky to keep attractive for long periods, as the fronds dry very easily. It enjoys damp soil, and also grows well in cracks on damp, shady rock walls. There are other species that grow in colder zones, like Adiantum pedatum, whose fronds have a beautiful ‘umbrella’ look.

Asplenium – Although many ferns in this group look fairly ‘normal’, the most striking are ones that have simple fronds like long green leaves. The most common in gardens is the Hart’s-tongue Fern, Asplenium scolopendrium, which forms a cluster of foot-long leaves from a central crown. It’s very hardy, and often grows well in rock cracks. Indoors you will often see the Bird’s Nest Fern, Asplenium nidus, a beautiful sub-tropical fern that forms a big green ‘nest’ of broad leaves.

Athyrium – a large group with many garden plants in it, these are mostly deciduous ferns, and two are widely grown in gardens. The Lady Fern, Athyrium filix-femina, is a classic-looking fern that is 2 or 3 feet tall, making attractive clumps. Look out for the variety called ‘Lady in Red’ which has bright red stems. The other popular species is the Japanese Painted Fern, Athyrium niponicum ‘Pictum’, a beautiful smaller fern that has unique elegantly-divided fronds that are striking silver-green, with maroon-red stems, that color spreading into the fronds as well. Besides the original form there are several newer selections with other leaf colors. Check out the ‘Godzilla’ Painted Fern, which is a hybrid with leaves up to 3 feet long – a striking and majestic specimen.

Christella – even if you know ferns a little you might not recognize this name, which isn’t surprising. These ferns have gone through several name changes before ending up here. The one most often grown is the Southern Shield Fern, Christella normalis, which used to be known as Thelypteris kunthii. As the name suggests it’s a fern that does well in the heat and humidity of the southeast, where others fade away. It is a larger fern perfect for planting beneath trees and large shrubs, and in natural gardens.

Cyrtomium – if you like bolder plants, then these are the ferns for you. The pinnules are unusually large and leathery, giving these plants the name of Holly Ferns. The tough leaves also make these more drought-resistant, and create a striking, bold statement in your garden. For warmer zones choose the popular Japanese Holly Fern, Cyrtomium falcatum, and in cooler zones you can grow the very similar-looking Fortune’s Holly Fern, Cyrtomium fortunei.

Dryopteris – a very large group of ferns – up to 400 species are recorded – these are big, bold ferns that look great in the garden. The Male Fern, Dryopteris filix-mas is often seen (yes, it was once thought to be the partner of the Female Fern), with its bold, upright fronds. Also lovely is the Autumn Fern, especially in a variety that has amazing gold and orange new stems. Called Dryopteris erythrosora ‘Brilliance’, it’s a striking garden plant of great beauty.

Matteuccia – the Ostrich Fern, Matteuccia struthiopteris, is the only fern in this group, and it’s one that is well-known in northern gardens. A bold fern also called the Shuttlecock Fern, it has unique sterile fronds that are hardy and clenched-looking, forming interesting winter effects after the other fronds have died.

Osmunda – this is a small group most well-known for the tall Royal Fern, Osmunda regalis. Growing up to 6 feet tall this is one for the waterside, as it will grow right in water, and grow taller there too.

Polystichum – a very large group of ferns (about 500 species), growing all around the world, this is a rich group to dig into for gardens. The most common is the Soft Shield Fern, Polystichum setiferum, a European native that is most notable for the many selected forms with incredibly fine foliage, often like clumps of feathers. These are great for adding soft texture, and also for pot-growing, where their fine beauty can be admired up close. Another valuable one is the Tassel Fern, Polystichum polyblepharum, a medium-sized and easy-to-grow fern notable for the way the tips of the young fiddleheads arch over like tassels, instead of forming the usual ‘clenched fist’ look, It’s an attractive evergreen fern for damp shade.